Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

If you’re wondering what an NFT, aka Non-Fungible Token, is, well, you’re not alone. CryptoPunks and CyberCats are selling for six and seven figures and even Christie’s is getting in on the digital art action. So we’ve got questions…what are these digital items, why are people investing a fortune in them (and should you?), and what does that mean for the financial sector and the art world?

Featured Guests

- Buvaneshwaran “Eshwar” Venugopal, Ph.D. – Assistant Professor of Finance at UCF

- Carla Poindexter, M.F.A. – UCF Professor of Art

- Lory Kehoe – Director, Digital Assets & Blockchain, BNY Mellon

Episode Highlights

- 0:26 – Introduction

- 2:04 – What the heck is an NFT?

- 04:01 – What do I actually own?

- 05:58 – What’s actually in the blockchain?

- 11:33 – Why did the bank become interested in an NFT?

- 15:10 – When the world gets back to normal, will this all go away?

- 21:40 – What keeps you up the most at night about NFTs?

- 24:45 – 10 years from now are NFTs going to be around and what are they mainly going to be used for?

- 28:15 – Dean Jarley’s final thoughts

Episode Transcription

Paul Jarley: Eshwar, I’m going to start with you. What the heck is an NFT?

Eshwar Venugopal: I think the world is trying to figure it out.

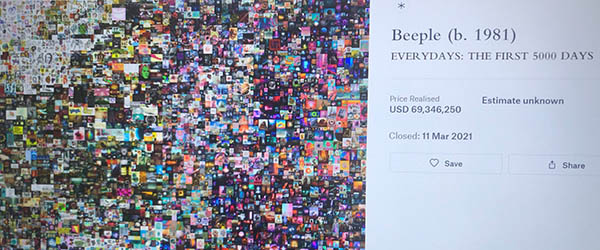

Paul Jarley: This here was all about separating hype from fundamental change. I’m Paul Jarley, dean of the college of business here at UCF. I’ve got lots of questions. To get answers, I’m talking to people with interesting insights into the future of business. Have you ever wondered, is this really a thing? Onto our show. (singing). On March 11th, CryptoPunk 3,100, a piece of digital art, sold for $7.6 million with an NFT. That broke the record set the day before by CryptoPunk 7804, which had sold for $7.5 million. Then on March 21st, Beeple’s the First 5,000 days sold for $69.3 million. Needless to say, people took notice. I took notice. Well, honestly, Josh told me to take notice. I was hesitant. This all seemed pretty esoteric. Techno geeks with stupid money doing techno geeky things, I thought.But then Forbes did an article. I noticed Christie’s auction house was involved. And so I started to send some emails and make some phone calls. My resident blockchain guy had an interest in this. The dean of arts and humanities, Jeff Moore, put me in contact with an artist interested in NFTs. The kicker was Jeff Stokes. Jeff is a member of my dean’s advisory board, with BNY Mellon, who put me in contact with their digital asset guy. If Alexander Hamilton’s bank was interested in NFTs, I figured I should be too. So to shed some light on this new phenomenon, we have with us today, Eshwar Venugopal, who is an assistant professor here in the finance department at UCF, Carla Poindexter, who is the professor of art at UCF, and Lory Kehoe, who is the director of digital assets and blockchain at BYN Mellon. Listen in.

Paul Jarley: Eshwar, I’m going to start with you. What the heck is an NFT?

Eshwar Venugopal: An NFT is basically a certificate of ownership of a digital group. Basically giving artists an ability to offer limited additions of their artwork. I’m going to use artists as an example over here, since we have Carla over here. But I have a problem with that, but I’ll come to it later on. But the idea is that you have a certificate of ownership and it is a limited edition product and it is more of a digital collection rather than a physical good. That’s how it has been envisioned. But things have been changing rapidly. These days, if you take some of the latest NFTs that are being minted, there is a physical aspect of it. One guy actually sold his house on NFT. So, things are a little bit blurry now, but if you take a look at it from a property perspective, it is just an ownership as a consumption good. That’s it.

Paul Jarley: Yeah. Let me be old school for a minute so I can understand this a little better. I can purchase an original Monet. I would go to someone who would be an expert in Monets who would say, “Yes, Monet really painted this.” And I would spend a kazillion dollars and I would put that Monet on my wall. But other people could reproduce that Monet. So when I buy the original Monet, I also didn’t really buy the intellectual property or the licensing of that Monet. All I bought was the original Monet. Carla, do you agree? That’s how this world used to work?

Carla Poindexter: Definitely. But you can also purchase the copyright.

Paul Jarley: But that would be separate though, right? That would be a separate buy.

Carla Poindexter: Definitely. Right. The Monet is probably, it depends on the piece, but sometimes it’s an open source image.

Paul Jarley: Okay, yeah.

Carla Poindexter: And sometimes it is not.

Paul Jarley: Okay.

Carla Poindexter: So, that is the difference.

Paul Jarley: I want to stay in the world I think I know, and then we’ll move to most of the world that I think we’re going to be in. The other analogy for me is, I’m a big baseball card collector.

Eshwar Venugopal: Oh, yeah.

Paul Jarley: And I’ve seen that a few… Akil Badoo, who’s this rookie for the Detroit Tigers, is actually issued a lot and in NFT. So I have a little bit of knowledge in the collectible area, only enough to be dangerous here. But the first thing I want to understand is what I actually own. I own a certificate of authenticity.

Eshwar Venugopal: Right. Let me actually give you an example with the baseball cards. So the other thing about NFT started with something called CryptoKitties. I’m not sure you know CryptoKitties.

Paul Jarley: Okay.

Eshwar Venugopal: So it’s basically similar to baseball cards.

Paul Jarley: Yeah.

Eshwar Venugopal: But a digital version with cats’ pictures on them. That’s how the entire thing started off. And essentially what you’re owning over there is the rights of ownership, or you can even think about it from a copyright perspective, through that particular kitty. The same way you have an authenticated baseball card, here you have a digital authenticated certificate of ownership. And it basically says that nobody else can claim ownership of this particular image, right? And the image is basically a set of lines and quotes, that’s it. You can claim in the public markets saying that, “I am the one who owns this baseball card or a CryptoKitty card,” and it can be easily verified and it can be verified digitally. If you have the baseball card, you have to call in, say, I don’t know what they’re called, but you probably have to call an authenticator.

Paul Jarley: Yeah.

Eshwar Venugopal: And somebody has to come in and verify the certificate of ownership and all of that. This just makes that process a bit easier and quick.

Paul Jarley: Let’s talk about what’s actually in the blockchain. If Carla had produced a work of art, for our listeners, Carla is a painter by trade, and she did a digital painting and she put it out for bid for an NFT. If somebody were to purchase that NFT, her artwork isn’t actually in the blockchain, correct?

Eshwar Venugopal: That’s correct.

Paul Jarley: Okay. Is it a link to the site? Is it a web address? What’s in the blockchain?

Eshwar Venugopal: So let me give you an example. I tried making an NFT last week. I took a picture of a monkey in Houston, I just uploaded it to Rarible and linked it to my Ethereum wallet and I tried minting. So when I minted, what happens is that Rarible has a unique code for my artwork or in this case, a picture of a monkey. And this particular picture gets uploaded into Rarible’s database, and there’s a link to it, and there’s a unique identifier. I can upload the full quality image or I can upload a lower quality image. It doesn’t matter, right? There’s a unique ID in Rarible for that particular thing. And that is the ID that gets embedded into the blockchain. It is not the actual image that is being uploaded into the blockchain rather a reference. And this reference is your identification for that particular image. So essentially no image is being uploaded into the blockchain, it becomes all the elements of the blockchain …

Paul Jarley: I’m placing a couple of bets here, I think. First I’m betting that the company has actually verified that you are the real creator of this, that you just didn’t pick something off of web.

Eshwar Venugopal: Right.

Paul Jarley: Right? And decide to throw that in. So what is the verification process like?

Eshwar Venugopal: That is where things get a bit mucky and I’m not clear on how Rarible does this. Rarible basically says that, or at least… All platforms definitely will verify whether this person has the raw art or if it’s a 3D art, they ask for the source file. If the source is there – it is this particular person, that’s something to verify the ownership. However, that’s not a foolproof way of doing things. I’m assuming that these platforms go ahead on the web and do an image comparison with whatever is existing out there and see if those links back to you. That’s one way of verifying. I’m not exactly sure how each platform was doing it.

Paul Jarley: Okay. Then secondly, I have to assume that that company and its website and address is going to continue in operation.

Eshwar Venugopal: Yes. That’s the hope actually. But if Dot Com and even the recent ICO woman busted any evidence, it may not be true in the long run. It may be true for the next five years, but who knows what’s going to happen in the next 10 years?

Paul Jarley: I’m on the fees issue….

Carla Poindexter: Yeah. The fee is supposed to be very high.

Eshwar Venugopal: Yeah. So the fees really depend on how much pressure is there on the blockchain at this point of time. Given that the last couple of weeks has been crazy and everybody’s buying a lot of Bitcoins and Ethereum, the pressure was high and therefore the fees are normally higher. On average, the fees have been in the range of $30, just to say that this image belongs to this person, so getting an entry into blockchain. And that particular part is $30, but if you want to actually list your items for sale, then you have to move to something that is an auction website. I used OpenSea and over there, the fee was again, roughly around $40 or something.

So just right off the bat, before I even sell it, it’s $80. And on top of it, there’s a 2.5% commission for Rarible and they take it over. The good thing about this is that, I get a royalty every time this image is being sold and resold, right? The first time I get 100%. But every time it has been resolved, right? If I’m a popular artist, probably Carla has more experience on this, if a piece is getting resolved, I probably get, I set it as 10%, but many people… You have the option to set it as a 20 or even 100%. That likely keeps growing. That this is not the case in today’s scenario. Yes, Spotify and other mediums allow artists to get royalty, but it does not set up in this way that you get lifelong royalties. And I think it’s not to lose…. 10% is a huge number, in today’s standards.

Carla Poindexter: That’s the beauty of it I think. Because when an artist sells an artwork, they receive whatever. But when that gets resold and resold the artist receives nothing.

Eshway Venugopal: Yeah. Especially the physical ones, their structure. Yeah.

Carla Poindexter: Right. And I think that’s why this has been invented. And I think that’s what is so exciting about it.

Paul Jarley: That’s very helpful, Carla. So the incentive from the artist is to be able to capture more of the future revenue stream in the resale market of the item.

Carla Poindexter: Definitely.

Paul Jarley: Is that right, Eshwar?

Eshwar Venugopal: Yeah. That’s correct.

Paul Jarley: Carla is that right?

Carla Poindexter: Definitely. That’s the beauty of the whole thing.

Paul Jarley: Okay.

Carla Poindexter: Because, imagine as a young person selling a piece of art for $1,000, and then later in your life, when you have established a reputation-

Paul Jarley: Right.

Carla Poindexter: … same piece gets sold for $20,000. The original artist never sees anything.

Paul Jarley: So Lory, why did the bank become interested in an NFT?

Lory Kehoe: We got involved and our interest, and why we’re interested in NFTs, is simple in many ways, it’s because our clients have started asking us about NFTs. And some of our clients in the wealth management side started purchasing NFTs, and they’ve got in touch with the bank to understand how we can custody them. And also, we’re getting early stage questions in relation to… Over time as these entities increase in value or some of them already valuable, and to Carla’s points just there, could they be used as items of collateral over time? So I think what we’re seeing is, NFTs has a potential. Are they a potential store of value as well as being something that, I guess, consumers may make, collect and engage with? For me on the NFT front, and this, I think, plays neatly into what Carla was talking about there, the way I think about NFTs is down to three things. So A-M-C. A, is accessibility. NFTs provide access to something which was… Especially pieces of art or very expensive pieces of art or luxury cars, as the case may be. And provides access to things like that that were unavailable for most of society, right?

I wish I could afford a Rembrandt, but I can’t, but I may be able to afford a Non-Fungible Token or a token representing a small part. So that accessibility piece is that term that gets used a lot. The second area is, M, and that stands for marketplace. It creates a marketplace where people can buy and sell these tokens or whatever you want to call these or NFTs. And then the final piece is community is C. And I think the community piece is actually the really interesting part of this. So growing up here in Ireland, I used to have football or soccer cards, in US, you have baseball cards and things like that.

Paul Jarley: [crosstalk 00:13:43] Baseball cards right there. You joined us late. Yeah.

Lory Kehoe: Exactly, right? And that was cool and I could trade those with my friends, but I was limited in terms of the folks I could exchange those with. And now, due to internet, obviously I could do that anywhere. But I think what Non-Fungible Tokens have brought about is, and which is really interesting, is that, it is the convergence and merging of the fan experiences in terms of physical and digital. And I think the Kings of Leon have done that incredibly well and I think they’re going to be… Actually, we’re only at the start of that happening so, the Kings Leon issued a bunch of NFTs-

Paul Jarley: Now we are into music. Yeah. Okay.

Lory Kehoe: Exactly. So they issued, as part of their latest album, a bunch of NFTs. And if you bought a bunch of them, built into the NFT, because it’s programmable, right? It’s a programmable piece of technology that you own. And this is really where the magic is, they built in this Willy Wonka and The Chocolate Factory Golden Ticket.

Paul Jarley: Golden ticket.

Lory Kehoe: Exactly. But what it did is that, the golden ticket gave you access, or will get you access, when we’re back doing all this great stuff, to a front row seat or to meet the band backstage. So what we’re seeing is this blending of fan engagement at a physical level, but also at a digital level. And I think we’re going to see a whole host of more of those initiatives, which are going to be unlocked through things like NFTs.

Paul Jarley: If I were to make the naysayers argument, it would be this, and this is where I started when I first discovered NFTs, there is stupid liquidity in the market right now. There’s a bunch of money running around, it’s got to attach itself to something and now it’s attaching itself to a digital asset because there ain’t enough things for it to attach to. And then, when the world gets back to normal, this will all go away.

Lory Kehoe: Geez. What can I say there? I think there’s a number of points. I think the world going back to normal, I don’t know what that world is going to look like, right? I think the genie’s out of the bottle post COVID. So, I think COVID has accelerated digital agendas for companies and for individuals all around the world. And I think people are interested in communities now more so than ever. We want to be part of something where we felt that we weren’t in the past. I’ll give you an example, if I go to New York and I go visit a museum or something like that, it’s interesting, I’ll go back home and I might tell my mom, “I was there and I saw this painting.” But actually, I now have a mechanism where I’m able to bring her into what that story looks like.

I’m able to purchase an NFT or a token. I’m able to pass it onto her. She’s now part of that story. She understands what that piece of art is, the history associated to it. And there is that community associated with it. She may want to purchase more tokens as the case may be, she may want to pass it on to somebody else. So for me, I think there’s value in that level of ownership. I don’t think it’s pure speculation. I think there is, it comes back to that community play. And I think we’re, we’re at the beginning.

Paul Jarley: Do you think the consumption side is more important than the investment side? Because part of what you’re talking about is consumer… What you’re talking about there is really varied in consumption. You’re purchasing the experience to consume that experience, which is different than, I think this asset is going to appreciate in value and I’m going to be able to sell it at a multiple some years in the future.

Lory Kehoe: And I think it’s both.

Paul Jarley: Yeah.

Lory Kehoe: I’m a regular Joe, if I see a potential for an asset to appreciate in value, and I can afford that asset. Well, I might go down that path and make that investment as the case may be, as part of a balanced portfolio, naturally. But, if there’s an opportunity to purchase something instead of buying, a MoMA pen, for example, right? I’m able to do something a bit more interesting. I’m able to pass that on. I’m also able to bring that person, the recipient of my gift, into the world of NFT. So they’re not only getting that NFT and the story about the painting, but I’m also bringing them into how this whole world works, which I think is also another angle.

So it’s an interesting one. I was talking to somebody yesterday about this and they were saying… They asked me, would I be interested in potentially purchasing a token or an NFT, which represents part of a forest where I’m actively contributing to the de-carbonization of an area. My gut response was, tell me more, tell me more, I’m interested. So I think the consumption side and the investment side, I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive actually. I actually think they could converge and that’s probably where you’ve got an even better story.

Carla Poindexter: I love what you’re saying, Lory, because that’s the whole thing about art. There’s the community and the activity of investing in an artist. And then there’s the other side, that more people tend to think about when they’re not interested in art, and that is the investment side. And I think the community side has to come first and then it becomes authentic. You were talking about reputable companies getting into this and looking into it. I love it when someone says, “Think about an NFT supporting an artist.” Someone purchases that token, purchases that artwork, and that allows the artist’s reputation to grow. And it’s not so much about the thinking that, Oh, someday I’ll get to pass this along and make money. Of course, that’s part of it, but entering into it, the point of the consumer, I think, is a good way to talk. Love it.

Paul Jarley: What do you think, Eshwar? I want you to react to my comment about stupid liquidity.

Eshwar Venugopal: Okay. Yes. There’s a lot of stupid liquidity over here. So, just let me take a step back and see where the NFT thing came from. So I mentioned CryptoKitties a while ago, right? The company that started this CryptoKitty build, the first thing that they wanted to do was do NFTs for real estate and they decided not to do it because of the regulatory pushback that they got. To both Carla and Lory’s point, community actually comes first in these things. This started off as a toy, as Chris Dixon would say it, and it has garnered a large enough community now that regulators have started taking notice of it. And as you mentioned, there was a lot of liquidity over there. And I wouldn’t buy the argument that things are going to go back to normal, or at least what it was before after the COVID pandemic just because people won’t have enough time playing with this thing. Because there’s already enough interest that this is now a self-following process. More and more people are getting into it. And it’s not going to be just with the art market. That’s what I said earlier.

Paul Jarley: Yeah.

Eshwar Venugopal: I have a problem with NFT being more hyped with the art market, rather IBM and IBV they have been in talks about putting patents, the entire patent system onto the NFT platform or as NFTs. And therefore trying to evaluate how much each patent is worth by buying and selling, there’s an active secondary market for that. And also even Academia, if you think about it. Academia can use the form of an NFT. If you think about it, we pay fees to the journals, to get our work published, and the journals ask universities to pay subscription fees and the authors themselves, in many cases, won’t have the copyrights to these things. Rather, if you put it on a NFT, you actually give credit to these authors, you can monetize it if the patent becomes a successful or an industry source uses your model.

Paul Jarley: What keeps you up the most at night about NFTs? Lory.

Lory Kehoe: Look, I thought some of the points that were made earlier there were great around… I think it’s difficult to purchase, right? I think the friction associated with them, that will get solved, right? That’s just technology in an early stage and a new wave of technology. That gets solved and gets solved quite fast. And I think it already is beginning to, right? And that’s number one. Number two, I think on the energy intensive nature associated with them. I think that is a consideration. But I also see that getting solved as we move away from the complex consensus mechanisms in terms of proof of work, to proof of stake, to other new ones that’ll emerge. So, although I don’t have a solution right now, I do think that that will get solved.

So that’s number two. And number three, I do think also as well, sometimes it could be, Eshwar was talking about this, it can be very expensive to actually purchase the token. Not the token price, but the actual process in terms of paying the gas fee or the associated fees to purchase it. So I think that’s another area that will get solved. As those three things move forward and get solved, that provides more people with an easier route in. And then also what happens, is that, you’ll have a bigger stock of NFTs to purchase. Not just art, not just luxury cars, but a range of things. And what keeps me up at night is probably, me sitting on the edge of my bed, being excited as to what’s to come, rather than fretting as to what will come each bar.

Paul Jarley: Eshwar, what about you?

Eshwar Venugopal: Well, Lory actually has covered one of the many things that keeps me up. Well, the first is, the overall impact that has. But the more important thing is the interaction of this digital economy with the existing one, how it is going to play out. Because it’s a matter of sustainability and stability over a period of time for… Because, yes, you have a new digital asset in place, but how is it going to impact the value of dollar over a period of time. It’s going to affect the larger economy, right?

Paul Jarley: Yeah, it is.

Eshwar Venugopal: Adoption is exponentially, especially, as I think Lory mentioned earlier, the COVID pandemic has just accelerated the way people adopt to digital assets.

Paul Jarley: Yeah.

Eshwar Venugopal: So the government has to step in and if they step in, and let’s say all of a sudden, they put a moratorium on Bitcoin or even the NFTs and they think that something is not right over here. What would happen to the existing money inside the system?

Paul Jarley: Right.

Eshwar Venugopal: To your point about stupid liquidity, a lot of people have put their money into the NFT system and Ethereum and all the other things over here. So what is going to happen over there? The interactions and the fall out, or the shake up before things settle down is, what both excites me as a researcher, but also keeps me up as an average citizen because I have a lot of money in NFTs as well. What will I do …

Paul Jarley: Can they be hacked? Can NFT systems-

Eshwar Venugopal: Yes. Yes.

Paul Jarley: 10 years from are NFT’s going to be around and what are they mainly going to be used for? What do you think Eshwar?

Eshwar Venugopal: I really wish they transform into something a little bit more reasonable. I wish they are not focused on just artwork and there’s a better way to mint these NFTs. My problem with NFTs is that it’s expensive, number one, and it is highly carbon intensive.

Paul Jarley: Yeah.

Eshwar Venugopal: So we cannot sustain a world where we are burning carbon so much just for the sake of digital art, even though I have high praise for art. So I hope that things change and we find a better technological way to implement these things and have artwork. But there are much, much bigger applications or use cases there for NFT. One of them is the patent system, the other one could be academic publishing, knowledge sharing. I’m hoping that the system would change from what it was. It’s a tie now I want to want it to become an actual thing.

Paul Jarley: Carla, what do you think. Do you think artists are going to be dabbling in this 10 years from now?

Carla Poindexter: I think so. I think it’s complicated now. I think the safety factor, the understanding of that clearing house that we talked about earlier on before Lory got in. Where does one go to even create that contract and create that token? How does that entity, the Christie’s or the intermediary, how does that all work? And I think once it becomes easier for people to understand, it’s a little bit like cryptocurrency right now, what are we going to really purchase a fraction of Bitcoin? Or, what was it, Doge?

Paul Jarley: Dogecoin.

Carla Poindexter: The Elon Musk you know.

Paul Jarley: Oh, right.

Carla Poindexter: Oh my gosh, it broke in half overnight. So I don’t know, I think we need to understand more about blockchain technology that the every… The artists are not, like you said earlier, most of us tend to… We need a step by step process here and we have to feel that these things are safe because the art market has never been a safe place for artists.

Paul Jarley: Lory.

Lory Kehoe: In 10 years, it will be the NFTs for many different things. Certainly not just art, I think music is one area. I also think in 10 years on, what you’ll see is that, these pieces, these NFTs will be used as financial instruments. I think what tends to happen at a retail level is that as more people adopt pieces of technology… And we saw this in Bitcoin, it happened at a retail level, and then eventually it reached a certain scale and then institutions really started getting interested in it, and then the regulators have to get interested in it because of the impact to the overall financial system.

With NFTs, if it reaches a certain scale, it will then be, okay, is there an opportunity here, at an institutional level, to help, for BNY Mellon, for our clients, we’ll provide services around NFTs. What other purposes can those NFTs serve? If we’re custodying them, it goes back to that collateral point. So I don’t think that’s going to be today or tomorrow, but I think that’s something that will happen over time. I think we’re at the start of the journey, if anything, we’re maybe coming towards the beginning or the end of the beginning, but we’re no means at the beginning of the end when it comes to NFTs.

Paul Jarley: It’s my podcast, so I get to go last. New technology is seductive. It gets you thinking about endless possibilities. Techno geeks creating and spending millions on digital art is a bit like fashion designers creating originals for the Paris runway. The designers and models get a lot of publicity, but your spouse ain’t wearing that on date night. It’s not practical. When moving from theoretical possibility to practical solution, I like to ask two questions: first, which problem does this solve? And if it does solve the problem, is this solution economically efficient? The Fisher Pen company allegedly spent a million dollars developing a pen that could write in space, but astronauts used pencils. Carla and Eshwar helped me to understand what problem NFT solve for the creator. It allows them to capture some of the appreciation in value of their creation in the resale market. But as Carla noted, creators need to understand and trust that the private guarantor of this contract will still be around and able to enforce this agreement at the time of resale. And since fees are high and tokenization is environmentally irresponsible, it seems a good option only for a small number of relatively well-known creators, not the masses.

Lory is a classic early adopter. He gave us three motives for potential buyers. Most fundamentally, NFTs have created a market by solving the ownership problem, you don’t want to purchase the digital equivalent of the Brooklyn Bridge from some scammer. Access and community are tougher sells for me. People want to be part of communities and will pay for access and exclusive events. But NFT seem a gimmicky solution to a problem with simpler known solutions like VIP tickets. This leaves access via fractionalization. Fractionalized tokens may make it easier than putting together a syndicate to purchase an expensive asset. But I’m not sure at what price point a fractional NFT is worth the cost of mining it. And there are a host of legal issues here that will need to be resolved.

In the end, I favor an explanation for the rise of NFTs, offered by Anil Dash, one of its creators, in a recent article in The Atlantic. NFTs for high priced art represent one of the few places people holding a lot of cryptocurrency can cash in their investment. They can’t buy expensive yachts, they can’t buy Teslas, depending on the day, but they can buy high priced techno art from artists. This will allow famous artists to get richer and retain some of the rights at resale, but the masses of artists and investors, well, they’re likely to be left behind. Eshwar called NFT a toy, I would add, a toy for the rich, at least for the foreseeable future.

Paul Jarley: So, what’s your take. Check us out online and share your thoughts at business.ucf.edu/podcast. You can also find extended interviews with our guests and notes from the show.

Paul Jarley: Special thanks to my interim producer, EriKa Hodges, who can’t get rid of this gig fast enough, Kenny Butcher, who helped us make this podcast possible, and the whole team at the office of outreach and engagement here at the UCF College of Business. And thank you for listening until next time, charge on.

Listen to all episodes of “Is This Really a Thing?” at business.ucf.edu/podcast.